Amauromyza karli in quinoa

Order: Diptera

Family: Agromyzidae

Introduction and damage

Amauromyza karli is an emerging stem-boring pest of quinoa, recently identified in Colorado, Oregon, and Idaho and confirmed in Canada. Although quinoa has been cultivated in Colorado since 1982, the discovery of A. karli marked a significant shift. From 2021 to 2025, A. karli infested all quinoa crops in Colorado, leading to a dramatic decline in acreage from approximately 3,000 acres in 2021 to just 160 acres by 2025. To date, there are no published reports of A. karli colonizing other food crops in the U.S. or internationally. As a result of the devastating outbreaks, this invasive pest poses an immediate threat to quinoa production, a niche crop valued for its high nutritional content and drought tolerance. Given quinoa’s potential to support climate-resilient agriculture, its continued cultivation remains important, making effective management of A. karli a pressing concern.

All agromyzid flies are herbivorous. While most species feed by mining leaves, some—such as Amauromyza karli—attack stems instead. In quinoa, A. karli females deposit eggs inside stems, and the emerging larvae tunnel through the pith. This extensive feeding disrupts nutrient transport, weakens structural integrity, and often leads to lodging, reduced yield, and plant death. Before pupating in the soil, larvae create distinctive exit holes on the stem surface. In Colorado, this type of injury has caused severe declines in quinoa production.

Quick Facts

- This stem-boring fly was recently (2021) discovered in quinoa in the United States (first found in Colorado) and has also been confirmed in Canada.

- In 2021, infestations were present in all of quinoa grown in the San Luis Valley of Colorado. These infestations have either caused severe yield loss or destroyed the crop entirely. As of 2025, only 160 acres remain.

- Early research results indicate that the population levels of this pest are correlated with acreage of quinoa, suggesting that areawide rotation, or alternating years when quinoa is grown, may help alleviate severe outbreaks of the fly.

Exit hole in quinoa stem caused by larvae of A. karli. Image credit: Adrianna Szczepaniec, Colorado State University

Quinoa pith destroyed by A. karli feeding. Top: healthy stem with intact pith. Bottom: infested stem showing pith with frass due to larval feeding; larvae are often found in these galleries. Image credit: Neha Panwar, Colorado State University

Quinoa pith destroyed by feeding of A. karli. Image credit: Patrick O’Neil, San Luis Valley, Colorado

Description and life history

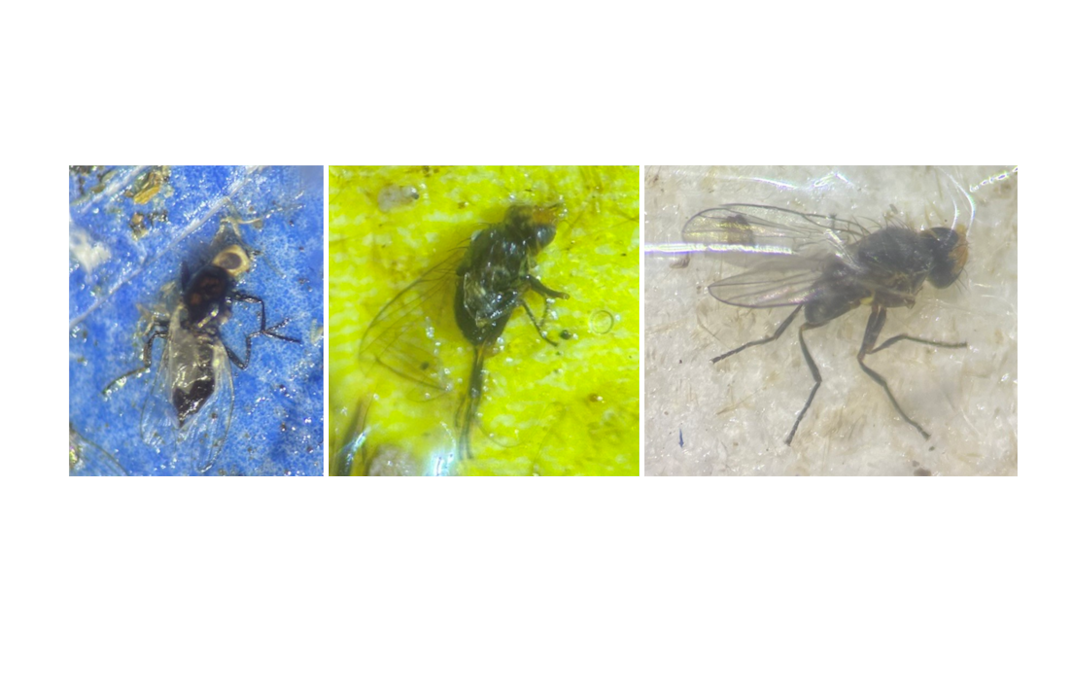

Adults of Amauromyza karli are about 3 mm long, with a dark brown thorax and abdomen and a distinct yellow head. They also have light yellow halteres (small knob-like structures that are a modified version of hindwings) and dark brown legs with narrow yellow ends near the joints. Larvae are white and grow to about 4.5 mm, while pupae are brown and roughly 2.5 mm long. The eggs of A. karli have not yet been observed, but eggs of closely related species are typically white, oval-shaped, and laid in clusters.

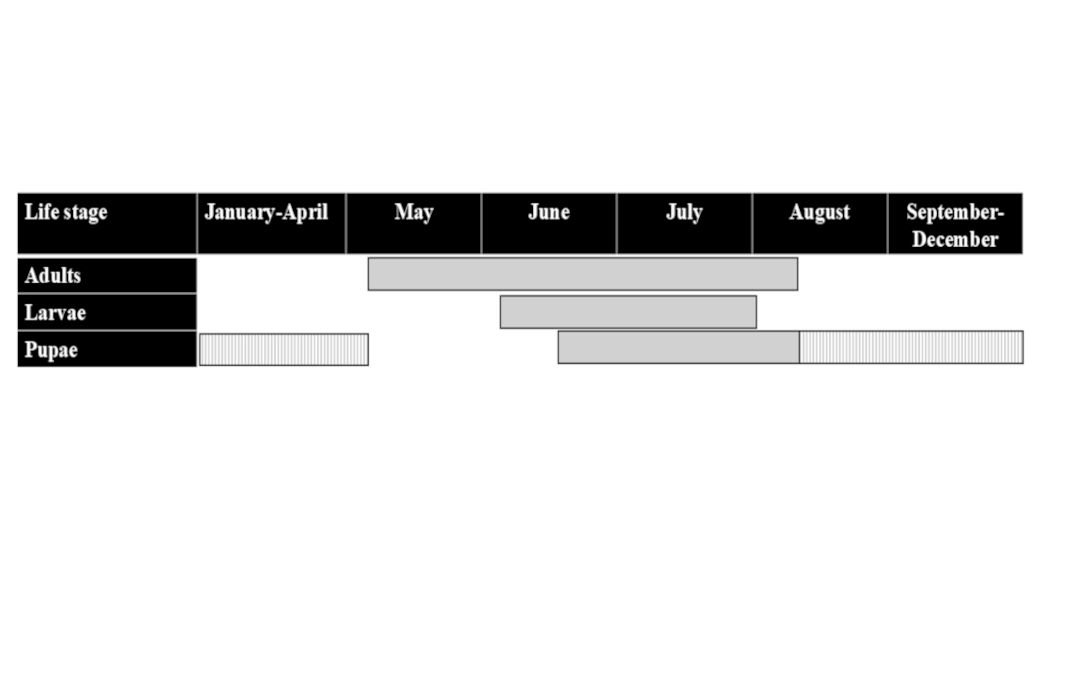

In Colorado, adult activity begins in May and extends through August with peak activity occurring in early July. During this period, adults mate and females lay eggs on quinoa. Like other agromyzid flies, females likely deposit eggs by repeatedly thrusting an egg-laying structure, called an ovipositor, into plant tissue until the eggs are laid. After hatching, A. karli larvae feed within quinoa stems from early June to late July. When development is complete, larvae exit the stems and pupate in the soil from late June through August. The flies overwinter in the soil as pupae from August through May, and adults emerge the following spring to begin the cycle again.

Adult A. karli collected from quinoa grown in Alamosa, Colorado. Distinguishing features include a yellow head and dark brown body with light-yellow halteres (small knob-like structures that are a modified version of hindwings). The legs are dark brown with yellow ends of the femur and tibia. Image credit: Tim McNary, Colorado State University

Larva of A. karli collected from quinoa stems grown in Colorado. These larvae feed within the plant stem of quinoa and cause plant death or severe yield losses. Image credit: Tim McNary, Colorado State University

Monitoring

Monitoring of A. karli in quinoa is effectively accomplished through several techniques that help determine the onset of an infestation and the extent of an infestation after A. karli presence is confirmed. To monitor adults, sticky traps can be used to capture flies; flies can then be identified and counted using a hand lens or a dissecting microscope. Blue sticky traps make identification of the flies easier, allowing for the bright yellow heads to be discernable. Fields can also be surveyed using a sweep net. Once A. karli adults are detected using sticky traps or sweep netting, quinoa stems can be destructively sampled by cutting plants at the base and splitting the stems to examine for the presence of larvae in the pith.

Estimated phenological development of Amauromyza karli based on field observations in quinoa fields in Colorado. The timeline is based on data from trap captures, sweep net sampling, larval counts, and number of exit holes observed on stems. Hatched bars represent overwintering pupae.

Neha Panwar and Adrianna Szczepaniec, Colorado State University

Images of adult Amauromyza karli captured on sticky traps of different colors (blue on the left, yellow in the middle, white on the right). Contrast between the blue traps and the bright yellow head of the fly is likely to facilitate effective monitoring of the fly without specialized magnification equipment.

Image credits: Neha Panwar, Colorado State University

Management

- Significantly lower numbers of flies in recent years are strongly correlated with lower overall acreage of quinoa, suggesting that areawide rotation of the crop, or alternating years when quinoa is grown, may be key to suppressing A. karli.

- Planting date modifications can help in managing A. karli. Planting in late April helps so that quinoa is past the most vulnerable growth stages before peak fly activity. Alternatively, delaying planting to late June/early July helps to reduce early-season exposure. However, late planting in arid climates can also stunt plants and reduce yield due to shortened season and heat stress, so planting dates should be selected based on local weather and irrigation.

- Resistant varieties have not yet been identified; however, there is anecdotal evidence that improving plant health with nitrogen and sulfur fertilization is associated with reduced fly pressure, suggesting crop vigor may lessen susceptibility to this pest. Further research is needed to confirm this effect.

- Flies can develop in other plants, such as lambsquarters, wild sunflower, and amaranth. Keeping these weeds suppressed inside fields and across field margins can reduce overall fly populations.

- Seed treatments with Beauveria bassiana, an endophytic entomopathogenic fungi, show promise as a management strategy by establishing the fungus inside plant tissues.

- No commercial insecticides have been effective against A. karli under field conditions.

Additional reading

Szczepaniec, A., and G. Alnajjar. 2023. New Stem Boring Pest of Quinoa in the United States. Journal of Integrated Pest Management. Available https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/14/1/5/7032941